“There is no development, in and of itself,

no development in general;

there is only the development of

this one or that one or that

third, fourth or

thousandth person.

There are as many development processes

as there are people in the world.”

Rudolf Steiner, Three Lectures on the Mystery Dramas, GA 125, lecture from 31.10.1910

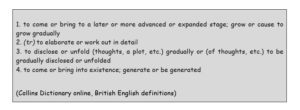

The word “development” already contains its meaning: Letting go [or unwrapping] of ideas or structures. What is development? The dictionary gives us the following explanations:

All children and adolescents develop differently from one another, as a result of “the unique interplay of socialization conditions and their unique self-concept and life plan” (Leu & Krappmann 1999, p. 11 et seq., cited in Prengel 2010, p. 30), which represent each child’s distinctive personality.

Individual differences account for high variability in development processes (Largo 1999, p. 25 et seq.; Porter 2002, p. 9), and inclusive schools must provide a suitable learning environment for these differences. Children and adolescents differ, creating classes with mixes of sexes, languages, social or ethnic heritages, health conditions, academic levels, previous experiences, etc. In an inclusive school, variety is planned for, with opportunities and the right to individual development. Varying starting points allow the children and adolescents to learn from one another in a common learning environment, and to develop together and help each other, as long as their teachers support this.

If we study the observations of Remo Largo, a Swiss pediatrician, we see how broad the field of development is. Remo Largo says he has done nothing in his life besides watch children in their development. For over thirty years, he worked for and directed the “Growth and Development” department of the Zürich Children’s Hospital. What he conveys through his researcher’s perspective is the variety that he describes based on decades of caring observation. It is our job, [as teachers], to look closely and ask, “What is going on with you? What challenge do you need to overcome right now? How can I help or support you?”

Remo Largo’s observations are important because he reveals his belief in a wide range of “normalcy” in child development, simultaneously frustrating our concept of “normalcy” and still trying to adhere to certain norms. We hear in his lectures and read in his books: Most of what we feel is “abnormal” or even “difficult” is neither. It is simply development. Quicker in some, slower in others. Some things remain different than we expect them to be, structurally speaking. So, what? What does that say? Variations between people and in individual people are already present at birth, and only increase throughout life. Each of the over seven billion human beings living on the Earth right now is unique (Largo 2017, p. 11 et seq.).

The concept of development is relatively young. According to Andrè F. Zimpel (2017, p. 68 et seq.), it is only since the 18th century that it has only been used in the sense of a gradual taking shape and unfolding. This has to do with the fact that until then, science was primarily defined by ontology (study of the nature of existence) (ibid.).

Baltes’ (1979) concept of development is based on traditional ideas that see development in the context of development-related changes. These behavioral changes caused by development have the following characteristics: They exhibit a natural sequence (sequentiality), they proceed in one direction (unidirectionality), they have a goal or end state (end state), their sequence is unchangeable (irreversibility), the changes are qualitative-structural transformations, and they have universal validity (p. 21).

Senckel & Luxen (2017) make it clear that their view of development is based on an idea of the human being that accepts a person’s current state of being without prejudice and unconditionally. This is the foundation that makes change possible. It also requires an empathic view of the other person, emotional presence, being present with oneself, and readiness. It requires a genuine offer of a relationship that is constructive and appreciative of the other person.

Reiser’s (1977) and Jantzen’s (1987) developmental ideas establish a developmental theory for all children and adolescents. Their decategorizing approach (Papke, 2015) provides a basic building block of an inclusive occupational theory for universal theoretical concepts of human development for teaching purposes. Requirements include an unconditional and positive willingness to accompany others in their development. It is easier to empathize with others if we perceive them in all of their facets and do not allow ourselves to be determined by assumptions (p. 17 et sec.). This view is based on Emmanuel Levinas’ basic philosophical assumption of the “fragility of human existence” (op. cit., p. 16).

There is one developmental theory for all children (including children with disabilities). Thus, the division into separate pedagogical jurisdictions, locations, approaches to development, educational goals and content is no longer warranted or justified (Papke, 2015). Children are agents of their own world acquisition and individual development (in dialogue with their environment and in communication with other human beings). Images of the self and the world are constantly subject to reciprocal transformation. Development is:

The significance of “development” for our diagnostic thinking and activity

Categories represent the “thinking tools” (Lanwer 2006, p. 23) in the diagnostic process, allowing us to gain understanding of the respective life and background situations. They represent scientific theories and the professional knowledge associated with them that form a frame of reference which can orient diagnostics and help develop diagnostic competence (loc .cit., p. 37). Expert knowledge about “development” is needed when it comes to orienting oneself in the diagnostic process, setting goals, being descriptive, making a comparison between general and special development, and reviewing situations/actions. Without this knowledge, questions and hypotheses regarding special talents or potential disadvantages or barriers in a life or learning situation cannot be posed or answered. It is also necessary in order to establish baselines, create personalized instruction in the learning content, and design learning environments.

All children want to become themselves.

Each child is unique.

Each child is special

– not a disruptive factor.

(Remo Largo)[1]

The Zurich Longitudinal Study tells us that there is diversity between children, as well as variety within each child, in regard to the following factors:

According to Largo, developmental profiles of ten-year-olds are so broad and diverse that standardization in families and schools cannot do them justice. And society is also intolerant of the completely natural differences between normal, healthy children.

There are some seven-year-olds who can read as quickly as others at sixteen. Around 500,000 German children cannot read at all, despite having gone to school. (Even the Pisa winner, Finland, has not been able to do away with the variety in reading competence – there are illiterate people there, as well.) Motor activity is highest between the ages of seven and nine, and boys are more active than girls. In any group of twenty seven-year-olds, the developmental range is +/-1.5 years: the developmental range of a seven-year-old corresponds to 5 ½ to 8 ½ year-olds. At age thirteen, girls’ development can correspond to any age from ten to sixteen, and boys’ development anywhere from nine to fifteen years!

The older the children, the more diverse they become.

… and the challenge to schools

We generally speak of “developmental diagnostics” when one or more standardized psychometric procedures—so-called development tests—are applied (Quaiser-Pohl 2010, p. 18). The tasks and goals of these tests are to determine the developmental status or level of a characteristic, i.e. a current state; to determine changes in developmental status at different points in time; to determine the rate of change; to determine the direction of change; and to describe the patterns of change (loc. cit., p. 22).

According to Remo Largo, boys are discriminated against in the school system based on development. However, the issue can only be solved in schools, through socialization and equal opportunities. Working on an individual level is important!

Goals of a child-oriented school:

Child-oriented learning is self-determined, active and selective. We cannot eliminate weaknesses, and it doesn’t help to dwell on them. What is important is how a child can best manage to handle them.

It is about:

There is a difference between what children should learn and how they learn, and what is actually done at school (often, self-confidence is destroyed and playfulness is lost). Therefore, it remains an absolute priority to respect the uniqueness of each child, as no child exists in order to fulfil expectations. Children belong to themselves! They need to become the beings that they are meant to become. Enabling this to happen is the task of parents and schools!

Deep knowledge of the principles of child development is an indispensable requirement for good teaching, if we are to take Rudolf Steiner’s statement at the beginning of this article seriously. The teacher training course he gave before founding the first Waldorf school, The Foundations of Human Experience (Steiner, 1919/1996), became foundational material for individual and group study on questions of child development principles.

The fact that our world is structured in a certain way does not at all mean that children need to develop according to this pattern. Especially with regard to institutional issues, broadening our individual perspective on children and adolescents has a relieving effect and is also immensely challenging: It is our task to see each individual in their own individuality and accompany them on their journey.

It is our task as parents and teachers to observe and to accompany. Relationship may be more important than teaching, as Eichelberger & Wilhelm write in their book, “Entwicklungsdidaktik” (2003, p. 13). It then follows, logically: “The point is no longer for children to follow the material, but rather for the instruction to follow the development and the developmental needs of the children.” (ibid., p. 13)

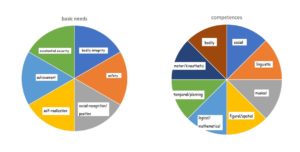

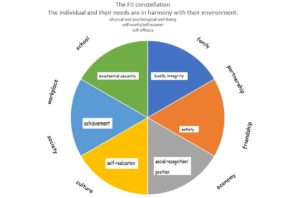

Remo Largo ultimately distinguishes between six basic needs and eight competences that develop with varying emphasis in each human being.

https://www.largo-fitprinzip.com/fit-prinzip.html

All human beings strive to live in harmony with their environment with their individual needs and talents. Remo Largo begins here, with a holistic view that understands the diversity among human beings, the uniqueness of each individual, and the interaction of individual and environment as the basis of human existence (Largo 2017, p. 347). With this understanding in mind, it is the task of educators to accompany children and adolescents on this path of development.

https://www.largo-fitprinzip.com/fit-prinzip.html

Rudolf Steiner does not separate methodology and didactics. He illuminates the connection between method, knowledge and the development of human abilities (Wiehl 2015, p. 13).

I never compare one child to another,

only each child to itself.

(Johann Heinrich Pestalozzi 1740)

References:

Ayres, J. A. (1984). Bausteine kindlicher Entwicklung. Berlin/Heidelberg/New York/Tokyo. Springer.

Baltes, P. B. (1979). Entwicklungspsychologie der Lebensspanne. Stuttgart: Klett-Cotta.

Brand, I., Breitenbach, E. & Maisel, V. (1988). Integrationsstörungen. Diagnose und Therapie im Erstunterricht. Würzburg: Marienverein.

Collins Dictionary online, British English definitions. https://www.collinsdictionary.com/dictionary/english/develop (27.5.2021)

Eichelberger, H. & Wilhelm, M. (2003). Entwicklungsdidaktik. Alle Kinder gehen ihren Weg. Wien: öbv & hpt.

Gardener, H. (2008). Intelligenzen. Die Vielfalt des menschlichen Geistes. Stuttgart: Klett-Cotta.

Jantzen, W. (1987). Allgemeine Behindertenpädagogik. Weinheim: Beltz.

Lanwer, W. (2006). Diagnostik. Methoden in Heilpädagogik und Heilerziehungspflege. Schülerband. Cologne: Bildungsverlag EINS.

Largo, R.H.( 1999). Kinderjahre. München: Piper.

Largo, R. H. (2013). „Schulen der Zukunft“. Bildungskongress. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=rM2a8b8_s5c

Largo, R.H. (2017). Das Passende Leben. Was unsere Individualität ausmacht und wie wir sie leben können. Frankfurt am Main: S. Fischer.

Largo, R.H. http://www.largo-fitprinzip.com/fit-prinzip.html, from 9.1.2018

Leu, H.-R. & Krappmann, L. (1999). Subjektorientierte Sozialisationsforschung im Wandel. In: H-.R. Leu & L. Krappmann (Hrsg.), Zwischen Autonomie und Verbundenheit, pps. 11–18. Frankfurt am Main: Suhrkamp.

Papke, B. ( 2016). Das bildungstheoretische Potential inklusiver Pädagogik. Bad Heilbrunn: Forschung Klinkhardt.

Porter, L. (2002). Educating Young Children with Special Needs. London: Paul Chapman Publishing.

Prengel, A. (2010). Inklusion in der Frühpädagogik. München: Deutsches Jugendinstitut e.V.

Quaiser-Pohl, C. & Rindermann, H. (2010). Entwicklungsdiagnostik. München/Basel: Ernst Reinhardt/UTB.

Reiser, H. (1977). Integration psychoanalytischer Konzepte in die Arbeit mit Sonderschülern. In: G. Feuser, (Hrsg.), Behinderte Pädagogik, behindernde Pädagogik, verhinderte Pädagogik. Beiheft zur Vierteljahresschrift Behindertenpädagogik, Volume 4, Year 16, pps. 23-35.

Senckel, B. & Luxen, U. (2017). Der entwicklungsfreundliche Blick. Entwicklungsdiagnostik für normal begabte Kinder und Menschen mit Intelligenzminderung. Weinheim/Basel: Beltz.

Steiner, R. (1919/1996). The Foundations of Human Experience. CW 293. Dornach, Switzerland: Rudolf Steiner Verlag/ NY: SteinerBooks.

Wiehl, A. (2015). Propädeutik der Unterrichtsmethoden in der Waldorfpädagogik. Frankfurt am Main; Bern; Wien: Peter Lang.

Zimpel, A. F. (2017). Entwicklung. In: K. Ziemen (Hrsg.), Lexikon Inklusion, p. 68 et seq. Göttingen: Vandenhoeck und Ruprecht.

[1] All statements are taken from two lectures by Remo Largo, at the education conference Schulen der Zukunft 2013: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=rM2a8b8_s5c and at the Archiv der Zukunft on 2.10.2008: www.adz-netzwerk.de/files/docs/largo_individ_okt08.pdf.