The Teaching Profession

The future

that we want

we must find, ourselves.

Otherwise, we will get one

that we don’t want.

(Joseph Beuys)

Interjection[1]

“You should design all lessons meaningfully…” (Steiner 1919/1986, p. 90) is Steiner’s highest directive for teachers. He lamented the specialization of the world that also becomes apparent in classroom instruction, and appealed frequently to teachers to take the whole as a starting point in schools, or to start small and “expand…” topics “such that the threads are drawn into all aspects of human life” (Steiner 1919/1986, p. 164). He called on teachers to explore the stuff of the world in detail, and to make natural phenomena understandable to children. In this way, teachers have full responsibility for instruction. Steiner’s suggestions are not step-by-step instructions (Dühnfort 1992, p. 153).

“The ideal curriculum must trace the changing image of human nature in its becoming at different ages, but like any ideal, it faces the full reality of life and must adapt to it. This reality includes many things: the personality of the teacher, who stands in front of a class; the class itself, with every characteristic of each individual student; the time in world history and the specific location…. All of these factors modify the ideal curriculum and require adaptations….” (von Heydebrandt 1994, p. 11)

The idea of what a teacher is was changed by Waldorf education. Based on anthroposophy, the “wisdom of the human being”, Steiner undertook to awaken a new consciousness for teachers. Teachers who implement these contents should see themselves not simply as imparters of learning content, “they learn to see themselves as people who influence the health, physical development, psychological processes and awakening of spirit in their students through their teaching” (Leber 1992, p. 322).

The guiding principles for the teaching profession that were customary at that time were no longer sufficient:

“What is needed is the ability of such teachers who, out of an authentic and lively enthusiasm, can achieve an artistic and creative design.” (Wehr 1992, p. 57)

People with mental dynamism, who understood world political and concrete necessities, were needed. Steiner battled the old teacher status of a lecturing “Doctor” (Wehr 1992, p. 57 et seq.). He considered teachers’ attitudes toward the world and life as very important. They must have enthusiasm for their subjects, as this is transmitted through them into the children’s psyches (Steiner 1924/1996, p. 118 et seq.). For this task, every teacher needs inner flexibility, artistry (Steiner 1922/1990, p. 116), a lively interest and enthusiasm, as well as “mental elasticity” (Steiner 1919/1993, p. 16).

Steiner saw freedom and dedication (Steiner 1919/1986, p. 76), the “spiritual background”, and enthusiasm that is automatically transmitted to the children (loc. cit., p. 71) as important requirements for teachers. Personal interest in the subject and its imaginative preparation would make instruction lively (ibid.).

Steiner saw children as the book from which a teacher should study pedagogy (Steiner 1929/2000, p. 110). It was important to him that the human being be recognized and that the necessary educational measures be found with “intuition”, based on that recognition. A teacher is called on to create a relationship with each student with an open and “meditative soul attitude” (Wehr 1992, p. 86).

“Knowledge of the human being is what we should truly strive for, and, if I may use a religious expression, leave the rest to God. True understanding of the human being already makes a person a teacher….” (Steiner 1922/1990, p. 180)

For Waldorf teachers, what is important is not knowledge and thinking, but their powers of observation (Steiner 1929/2000, p. 147). Teachers must concern themselves intensively with individual students, as this supports students’ individuality. The Waldorf education perspective on individual learning is based on this.

“In this sense, the Waldorf school trusts that human beings are best educated by human beings, and that individual learning is best supported through the individuality of the teacher.” (Lindenberg 1992, p. 283 et seq.)

Steiner called on teachers to contemplate the whole human being (Steiner 1924/2000, p. 15). This means that teachers should look beyond childhood and clearly realize that they are educating the adults of tomorrow. In accordance with Waldorf pedagogy, teachers must consciously develop “knowledge of the human being” with respect to the child (Steiner 1924/1996, p. 61) that comprehends the entirety of a human life – not just the part the teacher deals with (loc. cit., p. 63).

In this way, Steiner made requests of the teachers based on his anthroposophy. He maintained that specific questions are characteristic for each age group, and these questions yield the leitmotifs for Waldorf school instruction (Dühnfort 1992, p. 150). In accordance with the principles of the education, teachers embody a role model for children from age 0-7, and an authority figure for children from age 7-14. It is only from age 14 on that independent judgment is instilled through the attitude of the teacher (Steiner 1906/1991, 6th lecture). In addition, Steiner gave precise instructions as to how teachers should handle the “temperaments”, the individual “constitutional types”, and the “elements of the human being” in classroom instruction (see Steiner 1921/1996, p. 34 et seq.), so that the students’ psyches and physical health are not harmed. The way in which teachers teach content to the children is crucial, as this experience is then transformed by spiritual forces during sleep (Steiner 1921/1996, p. 42 et seq.). Humor is an especially important device (Steiner 1992/1990, p. 117). Steiner saw education as an artistic synthesis.

He fought against abstract pedagogy that has abstract principles. For him, pedagogy was “an art of education”, in which teachers “penetrate into the essence of a human being and through this penetration […] become able to read in the human being the right thing to do in each individual case” (Steiner 1920/1985, p. 265). An artist does not proceed according to abstract rules – aesthetics has no rules. An artist “…must strive in each moment to be creative, original” (ibid.). This is also true for teachers. Steiner wanted his ”method school” to be understood in the context of this conception of artistic education. He called for active “efforts at understanding”, through which the teachers should continually recreate the “idea of a human being.” The teachers should test, question and further develop content and methods and develop pedagogical action plans individually, but should never pass on traditional ideas and formulas as content or use them as methods.

Apart from that, teachers should educate themselves, for example by controlling their own “temperaments”, as these can have strong effects on students if they act upon students in an uncontrolled fashion (Steiner 1924/1996, p. 64 et seq.). If they know about the different effects, teachers develop “the right respect, the right appreciation for what the teaching methodology, the living conditions of education should actually be” (loc. cit., p. 68). Freedom of teaching is a condition and prerequisite for fulfilling the mission of “education toward freedom.” Waldorf teachers should also be free from any kind of fanaticism (Steiner 1922/1990, p. 179). Idealism is required of teachers, but it should affect the children indirectly, not directly. Steiner spoke strongly against sentimental “idealism” (Steiner 1919/1986, p. 166 et seq.).

According to Steiner, collaboration and cooperation between teachers is crucial for the pedagogical work. Each teacher should teach the same students as much as possible, in order to accompany them more intensively. When this is not possible, he called on teachers to communicate closely with each other about the children, as this is the only way for the children’s development to really benefit (Steiner 1921/1996, p. 17). Such conversations can be especially fruitful when set up within the full faculty of teachers that teach any specific grade or class (Steiner 1975/1, p. 72).

The weekly, all-faculty conference is integral to the pedagogical work at all Waldorf schools. All teachers take part in it. This conference is the “soul of all instruction and education” – it is where the curriculum is created, the classes are structured, the children are discussed, etc. The teachers “delve deeply into the whole life of the school and everything that is intended to inspire this school life” (Steiner 1929/2000, p. 86). For this collaboration, Steiner believed it important for teachers not to criticize each other during conferences, as there are many different ways to teach well. What was important for Steiner was the exchange.

“It is less about criticizing these things – one can always do that. It is about putting such things forward and trying to understand and accept them.” (Steiner 1919/1994, p. 34 et. seq.)

Steiner established “golden rules” for teachers. A summary of what he wished from them:

“Devout gratitude toward the world that reveals itself in the child, combined with awareness that the child represents a divine riddle that we must solve with our pedagogical art. Educational methods practiced with love that allow children to instinctively educate themselves through us, so that we do not endanger the children’s freedom, which must also be respected where it is the unconscious element of organic growth forces.” (Steiner 1922/1990, p. 75)

In his closing words at the first course for teachers of the school newly founded in Stuttgart in 1919, Steiner emphasized that the teachers must adhere to four things:

“The teacher is a person of initiative in the large and small whole.”

“The teacher should be a person who is interested in all worldly and human existence.”

“Our instruction will only be a manifestation of truth if we are careful to strive for truth in ourselves.”

“The teacher must not dry up and stagnate.” (Steiner 1919/1986, p. 193 et seq. and 1919/1994, p. 184 et seq.)

This demand for universality (Ullrich 1986, p. 139) that emerges for a teacher points to a foreseeable overextension that all Waldorf teachers risk if they take all suggestions in this chapter as equally important. The bottom line must be: Every teacher must choose and decide where they will place their personal emphasis. Steiner called for long periods of teaching as a class teacher, as he believed that the children’s psychological development would suffer if the teacher with whom they have principal attachment changes yearly (Steiner 1919/1986, p. 89 et seq.). A teacher keeps her or his class, so that she or he can achieve a “more intimate knowledge of the students” (Steiner 1975/1, p. 127). For Calrgren, the eight-year period class teachers remain with their class creates a community that offers a “home” (1990, p. 113). The goal of the eight-year class teaching period is to have “trust in an admired and loved authority” (Seitz & Hallwachs 1996, p. 149). This teacher is a “travel guide” (ibid.) through the second seven-year period of life. Da Viega (2006) now sees the “concentration of knowledge in one person” (p. 42) for eight years as outdated, since the “specialization and fragmentation of knowledge” has changed enormously in the last hundred years. In this context, he calls for scientific research into the length of the class teaching period and new approaches to solutions (ibid.).

A contemporary study on the student-teacher relationship in Waldorf schools (Helsper et al., 2007) opens up a qualitatively new perspective on the eight-year class teaching period, which, according to the authors’ analysis, is defined by succession and authority in the lower and middle schools (loc. cit., p. 81). Various teachers at various Waldorf schools are observed in their different relationships to the students. This study focuses exclusively on the socio-emotional aspect of the relationships. In their results, the authors describe that regardless of the reasons for or against retaining the eight-year class teacher principle, it can only be successful if there is a “reflective dynamization and modification of the concept of authority” (loc. cit., p. 531). Responsibly designing this will be the challenge for Waldorf schools of the future.

Following the eight-year class teacher period, a class advisor takes over and specialized subject teachers accompany the class for the next four or five [depending on the country – transl.] years of high school. This creates the opportunity for identifying with the specialized subject teachers (Leber 1974, p. 215).

A Waldorf school teacher is positioned in the tension arc between

freedom – responsibility

art – expertise

The challenge is not to lose sight of these high standards and yet, at the same time, to allow loosening from them, so as not to fall into dogmatic hardening or simply “fill” a prefabricated role.

|

|

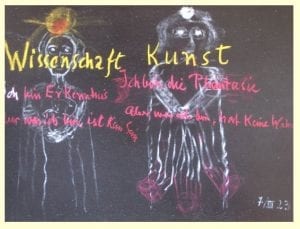

The teacher’s existence is a balance act between:

art – science – self-education

|

(science art)

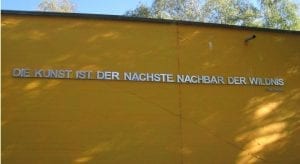

And yet, caution is called for, because…

|

(art is the next neighbour to wilderness)

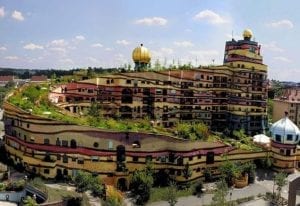

Our task is to change the house of learning…

|

|

|

Like the transformation that Friedensreich Hundertwasser undertook on many buildings.

Teachers need to accept children and their abilities and what they need to learn. This could mean

Proposition I

Irene Demmer-Diekman (2010) has shown in her research that professional identity development for teachers in the process of developing an appropriate attitude requires clear communication of knowledge. So, experiences with integration/inclusion, scientific research results, but also real-life integrative/inclusive school projects lead to more acceptance of inclusion-oriented settings. Only in this way can an end to categories in the school system be imagined and implemented.

Proposition II

References

Carlgren, F. (1990). Erziehung zur Freiheit – Die Pädagogik Rudolf Steiners. Stuttgart: Freies Geistesleben.

Da Veiga, M. (2006). Die Diskursfähigkeit der Waldorfpädagogik und ihre bildungsphilosophischen Grundlagen. In: H. P. Bauer & P. Schneider (Publ.), Waldorfpädagogik. Perspektiven eines wissenschaftlichen Dialoges (p. 15-41). Frankfurt am Main: Lang.

Demmer-Diekmann, I. (2010). Wie gestalten wir Lehre in Integrationspädagogik im Lehramt wirksam? Die hochschuldidaktische Perspektive. In: A.-D. Stein, S. Krach & I. Niedeck (Publ.), Integration und Inklusion auf dem Weg ins Gemeinwesen (p. 257–269). Möglichkeitsräume und Perspektiven. Bad Heilbrunn: Klinkhardt.

Dühnfort, E. (1992). Deutsch in Unter- und Mittelstufe. In: S. Leber. Die Pädagogik der Waldorfschulen und ihre Grundlagen (p. 135-147). Darmstadt: Wissenschaftliche Buchgesellschaft.

Helsper, W., Ullrich, H., Stelmaszyk, B., Höblich, D., Graßhoff, G. & Jung, D. (2007). Autorität und Schule. Die empirische Rekonstruktion der Klassenlehrer-Schüler-Beziehung an Waldorfschulen. Wiesbaden: Verlag für Sozialwissenschaften.

Idel, T.-S. (2007). Waldorfschule und Schülerbiographie. Fallrekonstruktionen zur lebensgeschichtlichen Relevanz anthroposophischer Schulkultur. Wiesbaden: Verlag für Sozialwissenschaften.

Leber, S. (1974). Die Sozialgestalt der Waldorfschule. Stuttgart: Freies Geistesleben.

Leber, S. (1992). Die Pädagogik der Waldorfschulen und ihre Grundlagen. Darmstadt: Wissenschaftliche Buchgesellschaft.

Lindenberg, C. (1992). Individuelles Lernen. In: S. Leber: Die Pädagogik der Waldorfschulen und ihre Grundlagen (p. 273-284). Darmstadt: Wissenschaftliche Buchgesellschaft.

Seitz, M. & Hallwachs, U. (1996). Montessori oder Waldorf? Ein Orientierungsbuch für Eltern und Pädagogen. München: Kösel.

Steiner, R. (1906/1991). Vor dem Tore der Theosophie. GA 095 (TB 659). Dornach/Switzerland: Rudolf Steiner Verlag.

Steiner, R. (1920/1985). Geisteswissenschaft als Erkenntnis der Grundimpuls sozialer Gestaltung. GA 199. Dornach/Switzerland: Rudolf Steiner Verlag.

Steiner, R. (1922/1990). Geistige Wirkenskräfte im Zusammenleben von alter und junger Generation. GA 217 (TB 675). Dornach/Switzerland: Rudolf Steiner Verlag.

Steiner, R. (1919/1993). Allgemeine Menschenkunde. GA 293 (TB 617). Dornach/Switzerland: Rudolf Steiner Verlag.

Steiner, R. (1919/1986). Erziehungskunst. Methodisch-Didaktisches. GA 294 (TB 618). Dornach/Switzerland: Rudolf Steiner Verlag.

Steiner, R. (1919/1994). Erziehungskunst. Seminarbesprechungen und Lehrplanvorträge. GA 295 (TB 639). Dornach/Switzerland: Rudolf Steiner Verlag.

Steiner, R. (1975). Konferenzen mit den Lehrern der Waldorfschule. GA 300 Band 1-3. 1. Auflage als Buch. Dornach/ Switzerland: Rudolf Steiner Verlag.

Steiner, R. (1921/1996). Menschenerkenntnis und Unterrichtsgestaltung. GA 302 (TB 657). Dornach/Switzerland: Rudolf Steiner Verlag.

Steiner, R. (1922/1990). Die geistig-seelischen Grundkräfte der Erziehungskunst. GA 305 (TB 604). Dornach/Switzerland: Rudolf Steiner Verlag.

Steiner, R. (1924/1996). Die Methodik des Lehrens. GA 308 incl. Die Erziehung des Kindes (TB 658). Dornach/Switzerland: Rudolf Steiner Verlag.

Steiner, R. (1929/2000). Der pädagogische Wert der Menschenerkenntnis. GA 310 (TB 749). Dornach/Switzerland: Rudolf Steiner Verlag.

Steiner, R. (1924/2000). Die Kunst des Erziehens. GA 311 (TB 674). Dornach/Switzerland: Rudolf Steiner Verlag.

Ullrich, H. (1986). Waldorfpädagogik und okkulte Weltanschauung. Eine bildungsphilosophische und geistesgeschichtliche Auseinandersetzung mit der Anthropologie Rudolf Steiners. Weinheim und München: Beltz.

von Heydebrand, C. (1994). Vom Lehrplan der Freien Waldorfschule. Forschungsstelle vom Bund der Freien Waldorfschulen. Stuttgart: Eigenverlag.

Wehr, G. (1992). Der pädagogische Impuls Rudolf Steiners. Stuttgart: Freies Geistesleben.

[1] The following paragraphs have already appeared in Barth, U. (2008). Integration und Waldorfpädagogik. Chancen und Grenzen der Integration von Kindern mit sonderpädagogischem Förderbedarf in heutigen Waldorfschulen. https://depositonce.tu-berlin.de/bitstream/11303/2332/2/Dokument_39.pdf.